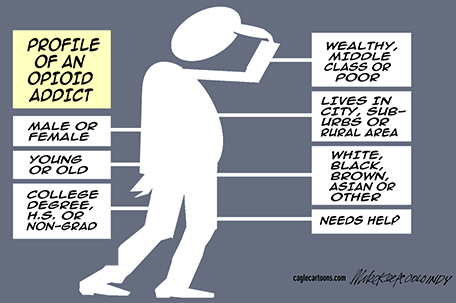

Black drug users lack something that white rural and suburban drug users don’t. That is political clout.

By Earl Ofari Hutchinson

On March 29, 2017, the mood at the White House was somber when #45 Trump signed an executive order establishing a commission charged with making recommendations on dealing with the opioid crisis. At the time of signing, all the talk by Trump and other administration officials was about a big ramp up in treatment, counseling, addiction recovery programs, and health services to alleviate the crisis. They, and the media, coined the term, “epidemic.” This suggested that it’s an illness, a sickness, a condition, but not a criminal offense. There was not one word from Trump or White House officials at the signing about more arrests, tougher sentencing and incarceration for offenders.

Trump appointed his close political backer, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, to head up the commission that would come back with the recommendations on dealing with the crisis. Christie made plain what the focus would be on, “What we need to come to grips with is addiction is a disease and no life is disposable. We can help people by giving them appropriate treatment,” he said.

The compassion, sympathy, and official search to find ways to help White opioid addicts that oozed out the White House that day was in sharp contrast to the memo Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a few weeks later. Sessions ordered U.S. attorneys around the country to get tough on drug crimes by demanding more convictions and jail time. Sessions wasn’t talking about White addicts, the ones whom the opioid crisis affected the most.

There were three reasons for that. One is politics. The opioid crisis slams suburban and rural areas, big swatches of which are Trump voter friendly. The second is that it has become a serious health issue with reports that there were more than a million hospitalizations last year from opioid addiction. The third is race. Countless studies have shown that Blacks use drugs about the same as Whites, using some drugs such as marijuana and powdered cocaine even less. Yet, for three decades, they have been the ones slapped with massive arrests, mandatory minimum sentences, and lengthy prison terms. They are the ones who pack America’s jails and prisons for drug crimes. They are the ones who will again be prime targets when Sessions reignites the drug war.

Whether it is cocaine, marijuana or the heroin surge in the rural areas and the suburbs, the relatively few times that Whites are popped for drug use, the pipeline for them is never to the courts and jails, but to counseling and treatment, therapy, and prayers. Their drug abuse is chalked up to escape, frustration, or restless youthful experimenting. They got heart-wringing indulgent sympathy, compassion, and a never-ending soul search for rational explanations — or should I say justification — for their acts that are deemed crimes when the offenders are Black.

The brutal racial double standard rests squarely on the pantheon of stereotypes and negative typecasting of young Black males that continue to have deadly consequences in the assaults on and the gunning down of unarmed young Black males under questionable circumstances. The hope was that President Obama’s election buried once and for all negative racial typecasting and the perennial threat racial stereotypes posed to the safety and well-being of Black males. It did no such thing. Immediately after Obama’s election teams of researchers from several major universities found that many of the old stereotypes about poverty and crime and blacks remained just as frozen in time. The study found that much of the public still perceived those most likely to commit crimes are poor, jobless and Black. The study did more than affirm that race and poverty and crime are firmly rammed together in the public mind. It also showed that once the stereotype is planted, it’s virtually impossible to root out. That’s hardly new either.

Black drug users also lack something else that White rural and suburban drug users don’t. That is political clout. The instant heroin became a “crisis” among Whites, and now opioid an “epidemic,” arch GOP conservative congresspersons in whose districts the “crisis” and “epidemic” hit leaped over themselves to declare the problem a health problem. They proposed a litany of new initiatives to treat the problem as a health problem. Police officials quickly followed suit. Dozens of police departments have publicly invited heroin users who wanted help to stop in their local police headquarters even in many cases with drugs and needles in or on their person. They would not be arrested, but shuttled promptly to a treatment program, no questions asked.

There’s one final great cruelty in the glaring racial double standard on drugs. The reports and stats on opioid and heroin addition, the wrath of news stories and features, on it, and the calls for legislative action to deal with the problem, have not changed one whit the deeply embedded perception that drugs in America invariably comes with a young, Black face. Trump’s call for compassion and treatment for opioid addicts won’t change that.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is an author and political analyst. He is an associate editor of New America Media. His forthcoming book, “The Trump Challenge to Black America” (Middle Passage Press) will be released in August. He is a weekly co-host of the Al Sharpton Show on Radio One. He is the host of the weekly Hutchinson Report on KPFK 90.7 FM Los Angeles and the Pacifica Network.

Leave a Comment