By Nathan Gelgud

signature-reads.com

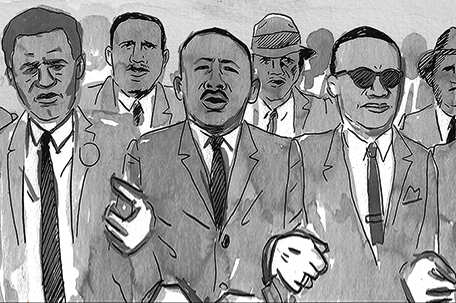

For Martin Luther King Day on January 18, countless schoolchildren will watch, read, discuss, and write essays about King’s famous “I Have a Dream Speech” delivered during the 1963 March on Washington. But in paying tribute to King this week, I’m thinking of a different speech, from a few years later. In 1967, at Riverside Church in New York City, King delivered his “Beyond Vietnam” speech to 3,000 people, and in the process, he infuriated and alienated many more.

The speech was King’s first public denunciation of the Vietnam War, and it represented a shift in his leadership and his focus. Many in his inner circle advised him against it, and many leaders in the Civil Rights Movement thought it was a grave mistake. In denouncing the war, King was—by short extension—denouncing President Lyndon Johnson, who was considered by many to be the greatest and most powerful ally of Civil Rights.

In “Beyond Vietnam” King addresses exactly why he can no longer remain silent about the unjust war in Vietnam. Perhaps his most important reason is that he realized he could no longer advocate nonviolence if he didn’t take a stand against the worst kind of violence being committed in the name of the United States across the Pacific. He says that in speaking around the country, he’d been confronted by questions from young black men who were being drafted to go fight in the name of the United States. The point became clear: “If you’re so against violence, why haven’t you said anything about this war?”

And so King came out against the war, and the next day the news media came out against him. According to Tavis Smiley, who made a documentary about the speech, 168 newspapers denounced it the next day, including the Washington Post and the New York Times. This stand against the war was not a case of King sensing a shift in the political climate and attaching himself to it. It was inconvenient and risky.

It also signaled a shift in King’s interests and represented a moment of great potential. What if the greatest leader of the Civil Rights Movement became an international leader? What if, beyond questioning who could sit where on the bus, he also questioned mass violence in the name of military self-defense? What if the very idea of black people fighting for an oppressive country became the issue? Those questions remain unanswered, as King was assassinated exactly a year to the day after delivering the speech. The timing might in fact have been a coincidence, but its symbolic significance is difficult to overstate. With his stand against Vietnam, King became more than a threat to bigoted mayors and Jim Crow laws in the American South. He became a challenger to the most powerful military in the world committing atrocities overseas.

Leave a Comment