By Kris Rhim

Before Jackie Robinson would become one of the most famous athletes ever by breaking the color barrier in Major League baseball in 1947, he started in the Negro Leagues.

In 1890, as baseball became a national sport and “America’s pastime” as we know it now, a “gentlemen’s agreement” was formed between major baseball team owners to restrict the game to white men only.

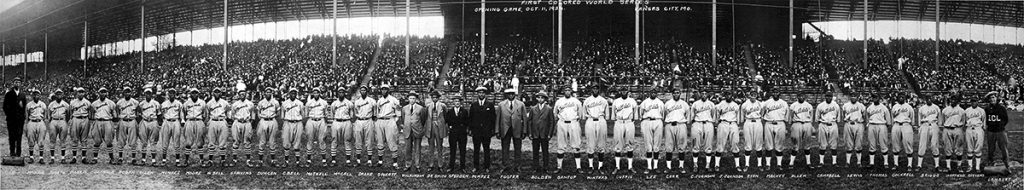

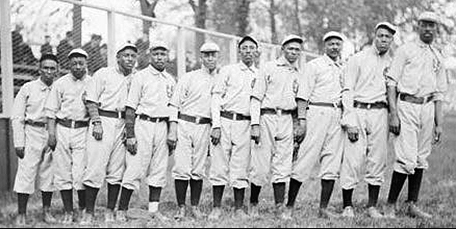

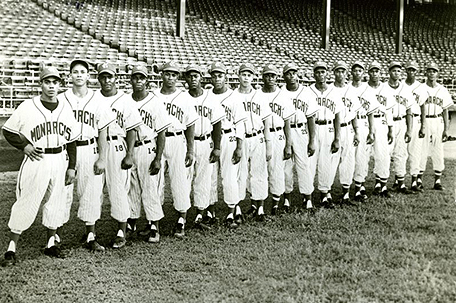

With the symbolic door to the major leagues shut, professional Black baseball teams began forming across the country. However, it wasn’t until Feb. 13, 1920, when Rube Foster held a meeting with eight Black baseball team owners at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, MO, that the Negro Leagues were born.

At its peak, these exciting teams filled the stands with fans across the country. By 1942, it was estimated that the Negro Leagues drew over 3 million fans. However, despite their success, they were always considered to be less talented than the white-only major leagues.

“No matter what (players) had done or how great the Negro Leagues were, the world said the highest level you could play [w]as the minor league,” Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, said.

As the Negro Leagues continued to flourish, the majors eventually came knocking. While many were happy to see Black players finally getting an opportunity, Kendrick described the feeling at the time as “bittersweet.”

“It was great because Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, but it also signaled the end of the Negro Leagues,” he said.

Due to the star players leaving, attendance dwindled until the league was forced to shut down for good in 1962.

In the major leagues, Black players did not disappoint.

Jackie Robinson would go on to win Rookie of the Year, then MVP two seasons later. Nine of the 11 National League MVP’s from 1949-1959 were former Negro League stars. At 42 years-old, former Negro Leagues pitcher Satchel Paige helped lead Cleveland to a World Series title.

“It makes all of us wonder, what if the doors had opened sooner?” Kendrick said. “Number one, how much better the game would’ve been? And I’ll say this with no level of uncertainty — the record books would be entirely different; there is no question about that.”

On Feb. 13, 2020, Kendrick, along with MLB’s commissioner, Rob Manfred and many others, headed into the same Paseo YMCA where Rube Foster founded the historic league to commemorate it’s 100-year anniversary. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum rolled out the plan for their year-long celebration. The MLB and MLBPA announced that they would make a $1M contribution to the museum to jumpstart the celebration.

However, just months later, the COVID-19 pandemic struck the country, and all of the celebration plans were canceled.

“It was heartbreaking,” Kendrick said. “We had invested so much time, and the magnitude of this occasion — to use a bad baseball analogy — coronavirus was that big nasty right-hander on the mound who just threw one high and tight and knocked me down. Now, you got to get back up, dust yourself off, get back in the batter’s box, and figure out how you’re gonna hit it.”

On June 27, the MLB was set to honor the Negro Leagues by having each team wear the Negro League centennial patch on the sleeve of their jerseys, in-stadium celebrations, and all teams were going to tip their cap as a salute to the leagues.

While most of the events for the 2020 celebration were pushed to 2021, Kendrick decided that the “Tipping of the Cap” could be salvaged.

The museum launched a virtual campaign, which started with four former U.S. presidents: Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Jimmy Carter, and George W. Bush. The virtual celebration quickly went viral with celebrities like Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Billie Jean King, and more joining.

Clifford Brown, the last surviving member from Philly’s Negro League team, the Philadelphia Stars, tipped his cap from his home in Tampa, Florida. Brown played for the stars from 1949-1951.

“In our sport, there is nothing more honorable a baseball player can do than tipping his cap. That’s the ultimate form of respect.” Kendrick said. “I’d be lying to you if I told you I thought it was going to take off the way it did. It just absolutely exploded, and it’s amazing how many people have embraced the campaign.”

For next year’s full celebration, Kendrick said the museum has a plan in place that will include education on the leagues and be headlined by a gala in November.

“This centennial was such an important milestone for Negro Leagues baseball,” he said. “We believe that the formation of the Negro Leagues a century ago is one of the most important occurrences in American history. This story is so much bigger than the game of baseball. At its crux, the story of the Negro Leagues is a story of the employers of economic empowerment; it is a profound story of unprecedented leadership that emerged as a result of this leagues’ success and ultimately, the story of the social advancement of America.”

“Jackie’s breaking of the color barrier was the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement in the country,” he continued. “This is before Brown vs. Board of Education, this is before Rosa Parks’ refusal. Martin Luther King was merely a sophomore at Morehouse College, and President Truman would not integrate the armed forces until a year after Jackie.”

For more information about the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and its programs, visit: www.nlbm.com.

Leave a Comment