ABOVE PHOTO: Artist Norman Lewis at the easel. (Photo: Courtesy PAFA)

By Natalie Pompilio

Associated Press

There are two questions Ruth Fine has heard repeatedly from visitors emerging from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ comprehensive retrospective of work by artist Norman Lewis.

“Those who don’t know his work ask, ‘How is it possible we didn’t know this painter?’” said Fine, a visiting curator, retired from Washington’s National Gallery of Art, who spearheaded the exhibition. “And those who did know of him ask, ‘How is it possible we didn’t know him better?’”

Many of the works in “Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis,” which runs through April 3, are on public view for the first time. The exhibition in the Academy’s main gallery includes 95 paintings and prints and is loosely chronological with six thematic sections: Into the City, Visual Sound, Rhythm of Nature, Ritual, Civil Rights and Summation.

“I think people are surprised by what they see, the variety,” Fine said. “This is the first chance many people have to get a sense of what this artist did.”

The Harlem-born Lewis, who died in 1979 at the age of 70, first gained attention in the 1930s for his figurative and literal depictions of struggles facing his urban African-American community. He then began to experiment with abstract impressionism, the realm of painters like Jackson Pollack and Willem De Kooning, whom he later befriended.

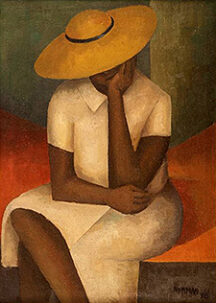

‘Girl with a Yellow Hat’ by Norman Lewis (Photo: Courtesy PAFA)

Some African-Americans artists tried to discourage Lewis’s change in style, seeing it as “a betrayal of what they felt a black artist was supposed to do,” said Moe Brooker, a well-known African-American artist.

“His friends said: ‘You can’t do this. You’re supported to talk about the difficulties. You’re supposed to talk about the oppression,’ but he refused,” Brooker said. “He said: “I’m black, yes, but I’m an artist. I will not be limited to doing the kind of work that you think I should be doing.’ He’s interested in being a human being.”

“He continued to search and struggle to find ways to communicate human issues, which is what art is really about,” Brooker said. “Whenever I see his work, I’m introduced to something new and exciting and different. I constantly come and find inspiration.”

While Lewis did find success during his lifetime – in 1955, he was the first African-American artist to be awarded the Carnegie International Award in Painting, and New York’s respected Marian Willard Gallery represented and exhibited his work – he did not get the same recognition many of his white peers enjoyed.

One item on display at the Academy is a 1977 letter Lewis wrote to powerful art dealer Leo Castelli, in which he noted others of lesser talent were enjoying greater success. “I’m a good painter,” he wrote. “I have talent. . I could be an asset to your gallery.” There is no indication Castelli responded.

In addition to race, Fine believes Lewis may have fallen off the art world’s radar because he does not have a signature image and can’t be pigeonholed. Lewis’ works “are beautiful and important. They are distinctive, which is the most important,” she said.

And there is more to the exhibition than Lewis’ paintings. A companion show featuring 30 of his etchings and lithographs is on view in a neighboring building.

Fine said she couldn’t put a monetary value on the displayed works, comprising pieces from private and public collections.

Leave a Comment