By Constance Garcia-Barrio

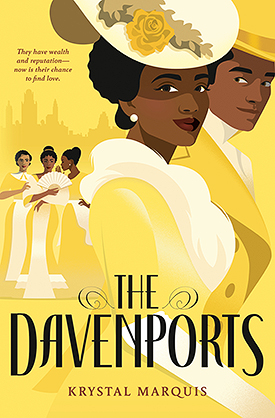

“The Davenports” by Krystal Marquis, published this past January, brims with romance, historic events, and family upheavals in 1910 Chicago.

The novel opens in a department store as Olivia, eldest daughter of the Black, ultra-rich Davenport clan, picks up a bolt of silk whose fabric spills over her dark skin like “a shock of sunshine.” It’s a joyous moment. “Anticipation bubbled in [Olivia’s] chest. The season of ball gowns and champagne had arrived.”

The family enjoys sumptuous living thanks to the patriarch, a former fugitive from slavery who, against monumental odds, has established a company that makes luxurious horse-drawn carriages. The Davenports — father, mother, daughters Olivia and Helen, and older brother John — live just outside Chicago on an estate so large that it has meadows where horses graze. The Tremaines, the Davenports’ close friends — mother, father, and daughter Ruby — seem to live well. However Mr. Tremaine has spent so much money on his campaign to become the first Black mayor of Chicago that their finances have become shaky.

Much of the scheming in both families arises due to the trouble of finding “…eligible [Black] gentlemen”— born into the right family, educated, and set to inherit a large fortune.

The Davenports’ and the Tremaines’ social standing cushions their lives, but it also means strictures. Young John Davenport would like to marry “infuriatingly beautiful” Amy-Rose, a biracial servant in the household, but his father responds to the proposed match with dire threats. Expected gender roles also hamper the young people. Helen, the younger Davenport daughter, finds her calling in an “unladylike” activity. “Kneeling in a puddle of [motor], she felt more at home than anywhere else.”

The novel points up issues that other Black Americans, as well as the Davenports, faced. Race riots in New Orleans in 1900, Atlanta in 1906, and Springfield, Illinois, in 1908, devastated those Black communities. Even Mr. Davenport’s money couldn’t protect his children from knowledge of the holocaust in Springfield, just 200 miles away, in which some 5,000 whites killed Blacks and burned down their homes and businesses. Thousands of Blacks left Springfield permanently as a result. This riot was a catalyst for the founding of the NAACP.

While Mr. Davenport has traveled lightyears from his days of enslavement, the past in one way still holds him hostage. He has lost touch with his brother with whom he escaped from bondage. Mr. Davenport meets monthly with “…men in the business of finding lost family members.”

Such searches sometimes had a Philadelphia connection. Many Black people seeking kin separated from them in slavery time turned to The Christian Recorder, published in Philadelphia. It is the oldest pre-Civil War periodical published by Black Americans and the official newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and where ads for these searches were placed. A notice in the February 4, 1865, edition of the newspaper, archived in the museum at Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, located 419 S. 6th Street, provides an example of such advertisements placed by Black families, which continued through the early 1900s.

“Information wanted of John Pierson, son of Hannah Pierson. When last seen by his mother he was about 12 years of age, and resided in Alexandria, Virginia…from which place his mother was sold to New Orleans… Through the reverses of this war she [reached] …New Bedford, Massachusetts…Any information concerning him or his grandmother, Sophia Pierson, will be thankfully received.”

Mr. Davenport also speaks of the National Negro Business League, founded in 1900 by Booker T. Washington to promote Black Americans’ entrepreneurship. Against this backdrop of fostering enterprise, Madame C. J. Walker’s “Wonderful Hair Grower” hit the market in 1906.

In “The Davenports,” descriptions of food and clothing recall seldom mentioned works set in Philadelphia in the 19th century about wealthy African Americans.

Joseph Willson, a rich Black man from the South, published a nonfiction book, “The Elite of Our People: Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia.” In 1857, Frank J. Webb, a native Philadelphian, published “The Garies and Their Friends,” a novel about an interracial couple from the South that resettled here. Such books, as well as “The Davenports,” help to counter the narrative of all Black people from that time period being downtrodden.

Marquis had that goal in mind when she wrote “The Davenports.” The story is “…inspired by a forgotten history…of Black success across Midwestern cities like Chicago during the early 1900s,” Marquis wrote in a note to readers. She adds that “The Davenports” is based on the life of Charles Richard Patterson (1833-1910). Born into slavery in Virginia, Patterson found his way to Greenfield, Ohio. By 1893, his company, C.R. Patterson & Sons, was making 28 kinds of horse-drawn carriages and buggies.

“The Davenports” has a lively pace and plot twists that will keep readers turning pages. Marquis creates sympathetic characters in the young adults who move the story, but the women have more grit and complexity than the men.

Billed as a novel for young people 13 and older, “The Davenports” will prove an enjoyable story for readers beyond that age.

Although set more than 100 years ago, “The Davenports” weighs questions that apply to any era: What do you owe your family? What do you owe yourself? How can you best use your gifts for your community?

“The Davenports,” by Krystal Marquis, Dial Books, $19.99

Leave a Comment