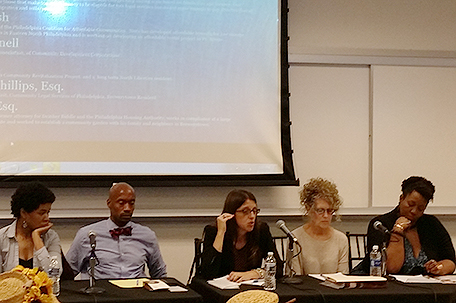

ABOVE PHOTO: Members of the panel of experts listen to and answer participants questions. (Photo credit: Amy V. Simmons).

Philadelphia has to figure out how to balance the competing interests of affordable housing and market rate development if it wants to keep it’s neighborhood feel. And the City doesn’t have a lot of time to come up with a solution.

By Amy V. Simmons

How does Philadelphia strike a balance between revitalizing neighborhoods through construction and development while maintaining housing affordable enough to allow longtime residents to enjoy the coffee shops, restaurants and other things that are the fruit of this new development?

And how does the city put together a plan to accommodate these competing interests without all of the distractions that prevent constructive dialogue?

The Fox Rothschild Center for Law and Society at Community College of Philadelphia recently held a dialogue on affordable housing and gentrification to talk about solutions and demonstrate how the process of deliberative democracy works.

“In today’s turbulent political landscape effective civic engagement becomes more important than ever, “said Kathleen M. Smith Esq., director of the Fox Rothschild Center for Law and Society. “The Fox Rothschild Center for Law and Society’s Symposium on Deliberative Democracy presents a proven way to cultivate citizens’ educated involvement in issues of societal concern.

In order to afford a one-bedroom apartment in Philadelphia, low-income workers have to work at least 83 hours a week to make the rent, said Blair Shaw, Esq of Merck and Company. However, there is a 10-year waiting list for affordable housing and original residents of neighborhoods like Northern Liberties, Passayunk and Mt. Airy watch as entire blocks change demographically.

Even some traditional neighborhood names are altered in the process, a move that many see as a cynical effort to erase the neighborhood’s diverse — or infamous reputation.

“Brewerytown’ used to be North Philadelphia,” Shaw said.

The purpose of the symposium was to help residents find ways to combat these problems using a method called deliberative democracy. The groups had to adhere to the core guidelines for deliberative discussion, which are that all arguments (pro and con) had to be:

1. Informed (and thus informative). Arguments should be supported by appropriate and reasonably accurate factual claims.

2. Balanced. Arguments should be met by contrary arguments.

3. Conscientious. The participants should be willing to talk and listen, with civility and respect.

4. Substantive. Arguments should be considered sincerely on their merits, not on how they are made or by who is making them.

5. Comprehensive. All points of view held by significant portions of the population should receive attention.

Robert Cavalier of the Carnegie Mellon Center for Deliberative Democracy, the keynote speaker for the morning session, had successfully initiated the use of the process in the City of Pittsburgh to address a variety of civic issues and helped participants with suggestions for ways to steer the discussion.

Each attendee was assigned to a lunch discussion group. The smaller groups — each containing no more than 10 people — had a moderator whose main job was to explain the process, distribute printed materials (which contained background information on the topic and hypothetical questions) and monitor the discussions between their group’s attendees.

After familiarizing themselves with the topic assignment sheet, the participants then discussed the topic – which in this case was affordable housing and gentrification — and formulated their own questions to be posed to an expert panel during the afternoon panel.

At one of the breakout groups, several participants shared their individual concerns about the effect gentrification was having on the city.

Eviction rates for all strata of African-American residents in Philadelphia are the highest in the region, averaging 24,000 per year, said panelist Rasheedah Phillips, Esq, Managing Attorney of LT Housing Unit at Community Legal Services of Philadelphia. She urged attendees — whether they were in directly affected or advocates for others who were — to become active in the process and take control of the situation by showing up at open zoning meetings and City Council.

All agreed that decent housing was a human right and societal obligation, and that the Philadelphia Housing Authority needs to be confronted regarding the practice of auctioning off available housing stock to foreign speculators and developers. They also agreed that if gentrification is a permanent fixture, then the wealth should be shared, and should include all strata of society.

They also expressed legitimate concern about the long-term rehousing options for original residents when developers move in, effectively pricing them out of neighborhoods that many have called home for over 50 years.

After lunch, attendees reconvened, led by a moderator and a panel of experts to continue the deliberative democracy process as a group. Each lunch discussion group had a designated member who was responsible for posing their group’s questions to the experts, although everyone was invited to make any points or counterpoints, as long as they followed the deliberative discussion guidelines.

For more information on the Program for Deliberative Democracy at Carnegie Mellon University, go to http://hss.cmu.edu/pdd/

Leave a Comment