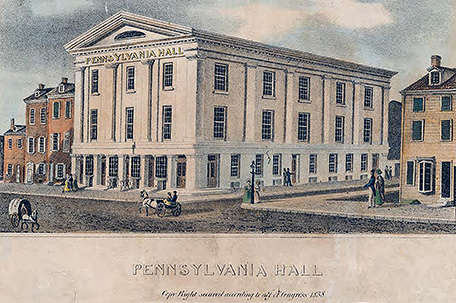

ABOVE PHOTO: The burning of Pennsylvania Hall, Philadelphia, PA, 1838. (Credit: The Library Company of Philadelphia)

By Constance Garcia-Barrio

On the morning of Monday, May 14, 1838, a small group of Black women from South Philadelphia, home at that time to many of the city’s African Americans, headed north, past Market Street’s smelly fish stalls and dye shops, to Pennsylvania Hall.

The Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women would soon begin in the stately new building on Sixth Street between Mulberry and Sassafras, about where WHYY stands now. Despite the excitement about the convention, only the second of its kind in U.S. history — the first had taken place in New York a year earlier — the women felt wary.

Conflicts over race, gender, and anti-slavery activism had stewed in Philadelphia for years. In December of 1833, men formed the American Anti-Slavery Society.

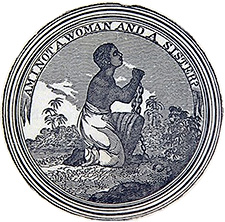

This group barred women. Undeterred, mere days later, a handful of Black and white women did the unthinkable.

The brazen “witches” — this is how many Philadelphians would have characterized them — launched the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). The women not only took a break from their kitchens and sewing parlors to have a say in the nation’s hottest political issue, but they also did so as an interracial group, a thing rare and scandalous in the 1830s. Their move “turned the world upside down,” as one observer put it.

Many of these smart, courageous women had the backing of supportive, well-heeled husbands. Quaker matron Lucretia Mott, wife of wool merchant James Mott, assumed a leading role in PFASS as did Charlotte Forten, wife of wealthy Black sailmaker James Forten, and the Fortens’ daughters: Sarah, Harriet, and Margaretta. All the women risked their safety with this radical stance, but the Black women perhaps more so. Competition for jobs fueled anti-Black feelings. In 1834, a white mob destroyed the homes of many Black residents and beat one man to death in front of his wife and children.

The daring women of PFASS pushed their projects. They provided money to support a school for Black girls. They also collected clothes for fugitives passing through Philadelphia on the Underground Railroad. PFASS financed those and other activities through fundraisers like its annual Christmas anti-slavery bazaar.

For that event, the women made and sold items like pies, anti-slavery alphabet books for children, and potholders embroidered with the words: “Any holder but a slaveholder.”

Due to many Philadelphians’ pro-slavery stance, PFASS and others opposed to slavery often scrambled to find places to hold events. Due to these roadblocks, several abolitionists, including women, paid to build a place where they could discuss slavery’s end. Two thousand shares at $20 each paid for the $40,000 cost of that building, Pennsylvania Hall. It was “…one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city,” according to “History of Pennsylvania Hall,” published in 1838. The anti-slavery convention would take place there, finished only days earlier.

The interracial gathering of 203 delegates from northern towns and cities turned up the heat on the issue of women, including PFASS, seizing a role in abolition.

Philadelphia’s mayor tried to cool things down by asking that only white women attend the convention, according to Laura H. Lovell, in “Report of a Delegate to the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, Held in Philadelphia, May, 1838,” Convention leaders turned him down.

The Black women from South Philadelphia and other places may have sensed the city’s simmering resentment.

Then again, seeing the luxurious details of Pennsylvania Hall might have swept away their anxiety, at least momentarily. Desks and other items “were made of Pennsylvania walnut of the richest quality,” Lovell wrote. “The chairs were lined with blue silk plush.”

A letter of support from former President John Quincy Adams may also have reassured the women.

By the next day, Tuesday, May 15, rumors flew around the city that the convention was promoting “amalgamation,” or race mixing, as it was then called. This fake news infuriated some Philadelphians, especially white men, who believed it.

Meanwhile, convention speakers stressed the abolitionists’ political clout. “The abolitionists are already in some states sufficiently numerous to control the elections,” Lovell reported one speaker as saying. The convention also passed a resolution that delegates would… “neither vote for, nor support the election of any man to any legislative office …who is opposed to the immediate abolition of slavery.”

As the convention forged ahead, threats against it mounted. By Wednesday, May 16, two days after the gathering began, ruffians started shouting and smashing windows. In addition, “a number of colored persons, as they came out, were brutally assaulted …” Lovell wrote.

By Thursday, a raucous crowd of white men and boys surrounded Pennsylvania Hall. Alarmed, the building’s managers asked Lucretia Mott to deliver “…a message …desiring the Convention to recommend to their colored sisters not to attend the meeting to be held in the Hall this evening because the mob seemed to direct their [sic] malice particularly toward the colored people.” The evening session was called off.

That night, the mob swelled to thousands. “The police were …ineffectual,” Lovell wrote.

Men — dockworkers, according to some historians — smashed Pennsylvania Hall’s doors with axes, then piled up wooden benches, opened the gas jets and lit fires. When flames roared through the building, the mob blocked the fire trucks.

“By 9 o’clock, the whole building was in one sheet of flames!!!” abolitionist Israel H. Johnson, of the Johnson abolitionist family of Germantown, said in a letter to his brother, Elwood, dated May 25, 1838. “The light was so great that it… [could be seen] at Germantown. Fire companies with engines came to the city, as did one from Chestnut Hill.”

“A fiend-like cry…went up as the roof fell in and Pennsylvania Hall burned to a shell,” according to “History of Pennsylvania Hall.”

Hungry for more destruction, the mob attacked the Shelter for Colored Orphans, 13th and Callowhill Streets, but the building was saved.

Some stalwart delegates met Friday, May 18, in a schoolhouse belonging to a PFASS member. In fact, anti-slavery women convened the following year in Philadelphia. The mob did not destroy the PFASS. The women disbanded only in 1870, after Congress passed the 14th and 15th Amendments, which recognized African Americans as citizens and gave Black men the right to vote.

But Philadelphia had lost forever Pennsylvania Hall, one of its most beautiful buildings. A plaque at 177 N. Independence Mall W. — 6th and Haines Streets — marks where the hall so briefly stood.

A version of this article ran in “Milestones” in February 2018.

Leave a Comment