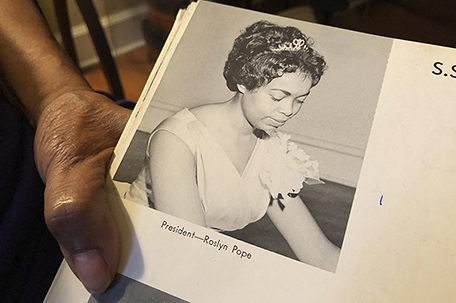

ABOVE PHOTO: In this March 4, 2020 photo, Roslyn Pope shows her Spelman College yearbook at her home in Atlanta. As a 21-year-old Spelman senior in March 1960, Pope wrote “An Appeal for Human Rights,” a document that made the case for the Atlanta Student Movement, a nonviolent campaign of boycotts and sit-ins by Black college students that protested racial segregation in education, jobs, housing, voting, hospitals, movies, concerts, restaurants and law enforcement. (AP Photo/Michael Warren)

By Michael Warren

ASSOCIATED PRESS

ATLANTA — Sixty years have passed since Roslyn Pope came home from Europe to a segregated South and channeled her frustrations into writing “An Appeal for Human Rights.”

The document published on March 9, 1960, announced the formation of the Atlanta Student Movement, whose campaign of civil disobedience broke a suffocating stalemate over civil rights in Atlanta and hastened the end of racist Jim Crow laws and policies across the region.

After all this time, Pope is deeply concerned that their hard-won achievements are slipping away.

“We have to be careful. It’s not as if we can rest and think that all is well,” Pope told The Associated Press in an interview last week.

The “Appeal” quickly became a civil rights manifesto after it appeared as a full-page advertisement in Atlanta’s newspapers. It was denounced by Georgia’s segregationist Gov. Ernest Vandiver but celebrated around the country, reprinted for free in The New York Times and Los Angeles Times and entered into the Congressional Record.

The idea was to explain why black students would defy their parents, professors and police by illegally occupying whites-only spaces. It decried the racist laws governing education, jobs, housing, voting, hospitals, theaters, restaurants, and law enforcement. It called on “all people of good will to assert themselves and abolish these injustices.”

“Every normal human being wants to walk the earth with dignity and abhors any and all proscriptions placed upon him because of race or color,” it said. “We do not intend to wait placidly for those rights which are already legally and morally ours to be meted out to us one at a time.”

“The time has come for the people of Atlanta and Georgia to take a good look at what is really happening in this country, and to stop believing those who tell us that everything is fine and equal, and that the Negro is happy and satisfied,” it said.

The students meant what they said, persuading Atlanta’s black families to boycott segregated stores and theaters and repeatedly seek service in places where the color of their skin meant they weren’t allowed.

Inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., they committed countless acts of nonviolent protest and were arrested by the hundreds throughout that spring and summer.

Pope’s role as the writer of the Atlanta Student Movement’s “Appeal” is well-documented. Less well known is how she came to write it as a 21-year-old student body president at Spelman College.

Born and raised in Atlanta, Pope said she did not know how it felt to be free until she was 20, when she spent a year abroad in Europe on a Merrill scholarship.

“There were no boundaries — no places I couldn’t go, no programs I couldn’t take advantage of, no limits to my existence. I could eat where I wanted — I couldn’t do that in Atlanta,” she said. “I felt like the shackles had been taken off me.”

Returning to life under Jim Crow felt suffocating, she said: “I was so miserable. I just didn’t know how I was going to stand it.”

She said she was drinking coffee with Julian Bond, who would later become a Georgia state senator, when his Morehouse College classmate Lonnie King approached, waving a newspaper article about a drugstore sit-in by four North Carolina A&T students the day before.

“It just clicked: ‘Why aren’t we doing that?’ we said to each other. And before the day was over, we decided to start a movement. We would no longer bear the mantle of inferiority,” Pope recalled.

Led by Lonnie King, an Ebenezer Baptist Church member but no relation to its famous pastors, they began mobilizing among the 4,000 students at Atlanta’s six Black institutions of higher learning.

When their college presidents realized they couldn’t stop them, they asked the students to explain their motives in a public document. Pope was named to the writing committee, but couldn’t persuade the young men to sit down and do the job.

“Roslyn was unable to corral us to work,” Charles Black, a Morehouse student who became an activist and actor, explained at a Black History Month event last month in Decatur, Georgia. “So Lonnie tells her, ‘write the damn thing.’”

Pope wrote it herself, longhand, pulling an all-nighter with Bond in the house of her professor, historian Howard Zinn, who had a typewriter.

“We didn’t have a lot of time,” Pope said. “Julian was typing it while I was handing him the pages.”

“Of course, it sent shock waves through the community,” she said.

“It became kind of a road map for our movement to take on all these things,” Black said.

Their campaign of boycotts and sit-ins, eventually including Martin Luther King Jr., forced white leaders to negotiate with the Black students to desegregate stores, theaters, schools and other institutions.

Pope went on to teach religion, music and English literature to generations of college students in New York, Pennsylvania and Texas while raising two daughters.

The “Appeal” has followed her all along, she said: “It’s just as relevant now as when I wrote it.”

Racism, Pope said, “is such obvious evil. And it seems to me that people don’t try to hide it so much anymore.”

“I just had a lovely great-granddaughter born in September, and I just hope things will be better for her,” she said. “Maybe we’ll have different leadership and people’s lives will have been changed. But I’m not terribly optimistic.”

Leave a Comment