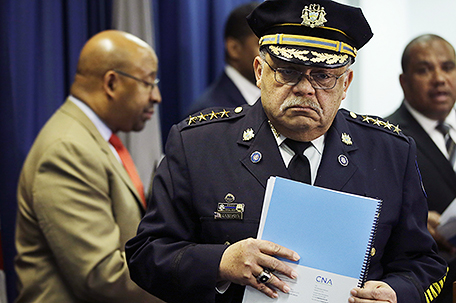

ABOVE PHOTO: Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey holds a newly released report during a news conference Monday, March 23, 2015, in Philadelphia. Poor training has left Philadelphia police officers with the mistaken belief that fearing for their lives alone is justification for using deadly force, the Justice Department said Monday in a review of the city’s nearly 400 officer-involved shootings since 2007. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

By Sean Carlin and Michael R. Sisak

Associated Press

Poor training has left Philadelphia police with the mistaken belief that fearing for their lives alone justifies using deadly force, the Justice Department said Monday in a review of the city’s nearly 400 officer-involved shootings since 2007.

Those shootings, involving mostly black suspects and 96 deaths, have contributed to “significant strife and distrust” between the department and the community and require intensive retraining in the use of force and community-oriented policing, a Justice Department assessment team said.

The review — already underway as police shootings last year in Ferguson, Missouri, and Cleveland heightened national focus on the issue — found Philadelphia’s investigations into officer-involved shootings lacked consistency, focus and timeliness and recommended a single, specially trained investigative unit to handle them.

It found wide disparities in crime scene photography and documentation, the use of typed notes summarizing interviews instead of audio and video recordings, and an internal affairs shooting team that waits months until after the district attorney clears an officer before interviewing him or her.

“What we’re doing here today is a start,” said Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey, who made similar recommendations this month for departments across the country as co-chairman of a White House task force on modern policing. “You can’t fix something until you recognize and acknowledge that it exists.”

Ramsey requested the federal review in May 2013 after four straight days of police-involved shootings in Philadelphia, three of them fatal. The review period coincided with a drop in fatal police shootings, from an eight-year high of 16 in 2012 to an eight-year low of four in 2014.

“We need to lower all the numbers,” Ramsey said at a news conference. “Folks need to stop killing each other.”

The Justice Department team found Philadelphia officers mistakenly perceived Blacks as a threat at more than twice the rate of Whites, contributing to community distrust, and recommended the department double community policing training at its academy, with a focus on cultural immersion and recognizing biases.

The assessment team found that 81 percent of suspects involved in shootings were Black, while 8 percent were White. For officers, 34 percent involved in shootings were Black and 59 percent wereWhite.

Philadelphia as a whole is 43 percent Black and 41 percent White, according to the 2010 census. The makeup of the Philadelphia Police Department is 34 percent Black and 56 percent White.

“These racial disparities have created a deep mistrust of law enforcement in communities of color,” said Reggie Shuford, executive director of Pennsylvania’s American Civil Liberties Union chapter. “The police department must begin to repair this relationship by emphasizing de-escalation and mutual respect in their interactions rather than relying on force.”

Officers interviewed for the assessment consistently mentioned fear for their lives as sufficient justification for using deadly force.

That notion, running counter to Philadelphia police policy, which does not include the word “fear,” and court rulings that require an “objectively reasonable belief” that lives are at immediate risk, appeared to stem from the department’s lack of regular, consistent training on its deadly force policy, the assessment found.

Annual firearms refresher courses focusing on tactics and targets vary widely based on instructor and include only cursory mentions of the deadly force policy, the assessment found.

Officers are required to complete a 20-question multiple-choice test on use of force at the end of their annual firearms qualification but just one of them pertains to deadly force, the assessment found. They last received any form of in-depth training on the subject in 2010.

The report recommends that officers receive more reality-based training and incorporate de-escalation techniques in the training.

“It’s not saying that there’s an absence of training but just that we need more,” Ramsey said.

A team of Justice Department researchers and analysts spent a year on the assessment. They developed 91 recommendations and will help the department implement them over the next 18 months and issue two progress reports.

The Justice Department’s announcement came days after the city’s district attorney declined to charge officers in a police-involved shooting in December of a suspect who reached into a car for a gun.

Residents protesting the decision and demanding the names of the officers fought with police and threw chairs at a community meeting Thursday. Ramsey called the display an embarrassment and said it reinforced his decision not to make the officers’ names public.

A small group of protesters outside the news conference Monday again pleaded with Ramsey to release the officers’ names. He didn’t answer them.

Leave a Comment