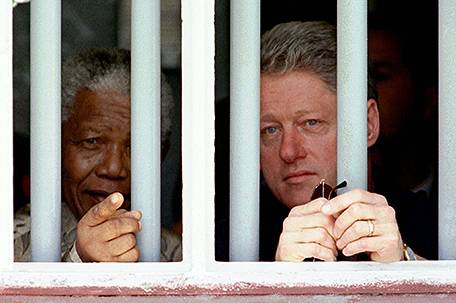

ABOVE PHOTO: Nelson Mandela and former US president Bill Clinton look to the outside from Mandela’s Robben Island prison cell in Cape Town, South African in 1998. A half-century ago Nelson Mandela was taken as a prisoner to Robben Island, 11 kilometers (seven miles) across the bay from Cape Town, where he would begin serving a life sentence for plotting to overthrow South Africa’s racist apartheid system.

(AP Photo/Rick Wilking, Pool, File)

associated press

A half-century ago Nelson Mandela was taken as a prisoner to Robben Island, 11 kilometers (7 miles) across the bay from Cape Town, where he would begin serving a life sentence for plotting to overthrow South Africa’s racist apartheid system.

The island jail was where Mandela became a worldwide symbol of resistance and where he spent 18 of his 27 years in prison, most of them toiling in the island’s limestone quarry. It is where he succeeded in rising above his inmate status by building productive relations with his jailers, first to improve the conditions for prisoners and ultimately to negotiate the end of apartheid.

Today at Robben Island, black former inmates work with white former guards to run the one of South Africa’s most inspirational tourist attractions. It’s a striking example of Mandela’s policy of reconciliation in action, with visitors hearing firsthand about his legendary leadership, tolerance and reverence for education.

Mandela encouraged others at the prison to study and take correspondence courses. Prisoners would gather in small groups for Socratic seminars.

“The University of Robben Island,” Lionel Davis, Mandela’s fellow prisoner, said proudly of the jail where he was incarcerated from 1964 to 1971.

“I was not the same person when I left the island, I learned so much,” said Davis, 76. “It was a university created by us, the political prisoners. And Mandela was a big part of that. We political prisoners even helped educate prison guards, who needed education for promotion.”

Many of the guards were white, and most of the prisoners were black. But to Mandela, “education was the enemy of prejudice,” and to those guards he thought would be open to persuasion, he offered lessons on the African National Congress, his liberation movement.

Now four ferries a day, guided by former political prisoners, bring hundreds of tourists to Robben Island. Some 320,000 people visited last year alone.

Robben Island had been a prison and leper colony for more than 300 years before it became a dumping ground for apartheid’s highest-profile foes.

During white rule, the wind-whipped 5-square-kilometer (2-square-mile) spit of land in the cold, gray Atlantic became a silent rebuke to the graceful city of Cape Town with its striking Dutch-inspired architecture and majestic backdrop of Table Mountain, and a source of pride to the city’s surrounding blacks-only slums.

Life as a prisoner was hard on the island. The diet was meager and inmates were allowed only two letters a year. News from outside would come sporadically — from occasional smuggled newspapers, or from visitors including Winnie, Mandela’s then-wife, on her two permitted visits a year.

Mandela’s 12 years in the quarry caused eye and lung problems that troubled him for the rest of his life, and by the time he emerged from prison, he had forgotten some of the simplest daily routines. Because shoelaces were banned in the jail, he did not remember how to tie them.

Robben Island also left a lasting mark by throwing together and uniting a black leadership.

The jailers who hoped to break the spirit of the anti-apartheid movement didn’t count on the discipline, ingenuity and optimism of the jailed. In the end, it was white rulers who ended up cut off. Subjected to international sanctions and boycotts, they concluded apartheid was unsustainable and reached out to Mandela to negotiate an exit.

Mandela was already prominent when the so-called Rivonia trial ended in 1964 with a life sentence for him and seven co-defendants found guilty of sabotage. He was a dashing figure — tall, handsome, with a trial lawyer’s flair for rhetoric and a royal pedigree and bearing. Fellow Rivonia defendants recognized his propaganda potential, encouraging him to write what would become the basis of his memoir, “Long Walk to Freedom,” during his time at Robben Island.

Prison authorities would not have allowed such a project, so Mandela wrote at night in secret in his concrete-floored, two-square-meter (yard) cell. Other inmates helped hide the manuscript and then smuggle it from the island.

Robben Island has loomed large in the life of Christo Brand, who went to the prison in 1978 to work as a jailer. “I was 18 years old and Mandela was 60,” said Brand.

Gradually a bond developed, so that Brand would smuggle in items that Mandela wanted — whole wheat bread and hair cream. Brand even sneaked in a baby so that Mandela could see his granddaughter Zoleka, now aged 33.

When Mandela became president in 1994, he remembered his guard and invited Brand to visit him at his offices.

Now Brand runs the Robben Island gift shop.

“The legacy of Mandela is here on Robben Island,” said Brand. “This prison has been turned into a place where people come and learn about how we can all get along. Mandela got what he was fighting for and he created a place where we can all live in harmony.”

Leave a Comment