By Constance Garcia-Barrio

Maybe seeing truth, like seeing beauty, depends on where you stand and what you know. That outlook could apply to many people’s impressions of the Black Panther Party (BPP).

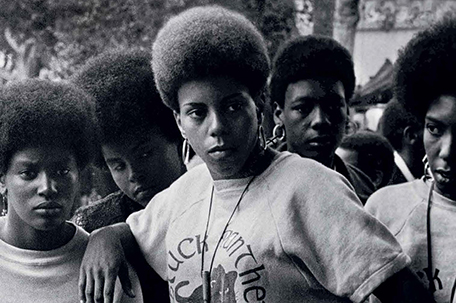

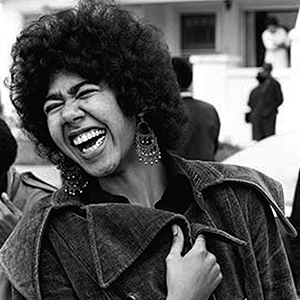

Founded in Oakland, California, in 1966, the BPP pushed for Black rights until its disbanding in 1982. One might consider the organization’s iconic founders, Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, and Eldridge Cleaver — author of the explosive memoir “Soul on Ice” — the force behind the Panthers. Yet, the book “Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party,” co-authored by former BPP members Ericka Huggins and Stephen Shames, highlights the crucial role of women as Panthers.

On March 22, in celebration of Women’s History Month, the Free Library of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Commission for Women, and the local chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) collaborated to present a panel discussion centered on the book.

The panel consisted of Shames and Huggins, who attended via Zoom. Former Panthers Regina Jennings, Ph.D., and Ethel Paris, both of Philadelphia, rounded it out.. Award-winning broadcast journalist and filmmaker Karen Warrington served as moderator.

Shames, who’s white, began by talking about the historical backdrop that led to his connection with the BPP.

“In 1954, when I was 7 years old, the Supreme Court decided that ‘separate but equal’ had to go,” Shames said. “In 1965, I was a student at Berkeley. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were selling books on the fringes of a march. I took some pictures of the event and later showed them to Bobby Seale.”

“Bobby asked me, ‘Can you cook?’ I said yes. Then he asked, ‘Can you sell newspaper?’ I said yes. And that was it,” Shames said.

His responses and his photos led to Shames becoming a photographer for the BPP. “Comrade Sisters” is his third book of photos featuring the Panthers.

Ericka Huggins, whose husband John held a key position in the BPP, spoke of women’s role in the Panthers. Women made up more than 60% of the BPP in the 1970s, according to Huggins.

“The Panthers realized that the government wasn’t providing basic needs of the community — that included Black people, Asians, Latinos, Indigenous people, and poor whites — and started programs like “Feed the Babies,” with free food for children,” Huggins said. “We did all kinds of programs. From 1973 to 1981, we ran the Oakland Community School tuition free. We had political education classes to inform the community. We had free medical clinics named after heroes and sheroes in our community. We gave out free clothes and shoes. Most of those programs were run by women.”

Communal life formed the heart of the BPP.

“We ate together,” Huggins said. “We worked together. We had the same purpose. We were free. It was exhilarating.”

For Huggins and for other Panthers, that life exacted a steep price. Her husband John Huggins, a BPP leader, was killed three weeks after their child was born. Warrington asked Huggins how she kept going after her husband’s murder.

“The face of the baby John and I had birthed kept me going after his death,” Huggins said. “I was devastated that John’s mother outlived him. I still am. Later, I was put on trial for a murder I didn’t commit. I was separated from my child. I knew that I had to so do something in that [prison] cell to keep my heart from withering. I taught myself to meditate. The way you meet challenges is as important as the challenges themselves.”

The FBI used many tools to end the Black Panther Party, Huggins said.

Philadelphian Regina Jennings, a poet and a member of the BPP, said that having had women in her family who resisted the status quo influenced her in joining the Panthers.

“My grandmother was a cleaning lady, but after she put away her mop, she operated a speakeasy. She was also a numbers runner,” said Jennings, who read a poem.

Panelist Ethel Paris spoke of how becoming a member of the BPP changed her.

“When I joined the party, I was quiet, but I got my voice and strength from joining the Black Panther Party,” she said.

Karen Warrington had a story to tell, too.

“My son was one of the youngest Panthers,” she said. “He mimeographed a newsletter. His sister was his minister of information. People would take a newsletter and drop a coin in the box.”

“Comrade Sisters,” available at the event, contains a foreword by Angela Davis, a preface by Shames, and an introductory chapter by Huggins. It consists of many brief essays by former BPP members and their children. Shames’ eloquent photos are people’s recollections form a kind of mosaic. For example, Kaye Casey, the daughter of Kaye Washington and Amar Casey wrote about her mother’s time in the Panthers.

“One of my mother’s most memorable moments …was being a teacher at the Oakland Community School,” Kaye wrote. “Decades later, my mom would talk about how she enjoyed working with the children there more than being a corporate lawyer.”

Ruth Wakabayashi-Kendo also recalled her time at the school.

“Since my focus was on education, I was invited to go to the LA Free Breakfast for School Children and help,” Wakabayashi-Kendo wrote. “That prompted me to join the Black Panther Party.” She had advice for the new generation of activists. “I would tell young women today to have the courage to believe in their worth and move forward when they don’t have all the answers.”

Comments in “Comrade Sisters” show the BPP’s global reach. Mere Meanata Montgomery, of Auckland, New Zealand, wrote about setting up the Polynesian Panther Branch.

The book helps to create a more inclusive image of the Panthers. Someone compared the popular view of the Panthers as a male-dominated organization with the experience of Ida B. Wells’ regarding the NAACP. Wells, an activist and journalist, took part in the NAACP’s founding, but wasn’t listed as a founder due to gender bias.

“Comrade Sisters” helps ensure a more accurate picture of the Panthers.

“We were on the ones who kept things moving,” Huggins said.

The panelists offered advice for today’s young activists.

“It’s important to know what your gifts are,” Ethel Paris said, “to discover your purpose.”

The panelists also mentioned that programs like the “Free Breakfast for School Children” can be replicated. In addition, they stressed the importance of building coalitions rather than working alone.

An audience member called for the School District of Philadelphia to make “Comrade Sisters” available in schools. Huggins mentioned she’d made a study guide.

While the book honors women’s roles, it also challenges descriptions like Wikipedia’s of the Panthers as “a Marxist-Leninist and black power political and criminal organization founded by college students.”

The Panthers encouraged self-definition, including writing our own history. Readers can thank Stephen Shames and Ericka Huggins for following that dictum.

Shames’ photographs — as well as artifacts from Temple University’s Blockson Afro-American Collection and the African American Museum of Philadelphia — will be displayed in the Central Library’s West Gallery through April 27, 2023.

To purchase a copy of the book, visit: www.accartbooks.com.

Leave a Comment