ABOVE PHOTOFifteen fugitive slaves arriving in Philadelphia along the banks of the Schuylkill River in July 1856, Engraving from William Still’s history UNDERGROUND RAILROAD 1872 with modern watercolor.

By Constance Garcia-Barrio

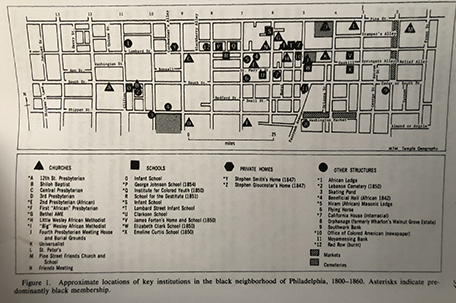

If the alleys that thread through Philadelphia from Broad Street to the waterfront, and from Locust Street to Catherine Street, could talk, they would tell little-known, rousing tales of the area’s Black history. Thanks to Michiko Quinones, 53, a historian and docent — or guide — and Morgan Lloyd, 25, a historian, consultant, and curator, some of the city’s cobblestone alleys have gained a voice.

Quinones and Lloyd have just launched a new Black history tour which they and members of the Black Docents’ Collective lead. The collective, a group of historians, seeks “to educate, empower, and heal” Philadelphia’s Black community by celebrating its “history, culture, and African values.” The walking tour spotlights the neighborhood previously mentioned.

“About 20,000 free Black people lived in Philadelphia by the late 1830s,” Quinones said. “They faced huge obstacles, including murderous mob attacks, yet they became a force in the life of the city.” “Lots of luminaries lived in this area,” Quinones said as she began the tour at 244 S. 12th Street, once the home of abolitionist, activist, and businessman William Still (1821-1902). Originally from New Jersey, Still worked at first as a janitor at 5th and Arch, then at the headquarters of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Later, he was president of the Vigilant Committee, a group that helped organize the Black community to provide food, clothes, shelter, and medical care for Blacks fleeing from slavery.

“He kept careful records so that family members could find each other later,” Quinones said. “One of Still’s own brothers, Peter, who escaped from slavery, was reunited with Still when Peter sought assistance from the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.”

Still took a huge risk in keeping the records since they provided proof that he was helping freedom seekers. If found, the document would have incriminated him. One story says that Still hid the record book in a graveyard to keep it from falling into the wrong hands.

Antebellum Philadelphia simmered with tensions, Quinones pointed out. The city was a commercial hub, a busy port. Ideas and energies sometimes clashed here.

“Black Philadelphia had a deep network of economic and political activism,” Quinones said. “You had Quaker abolitionists and Underground Railroad agents like Still on the one hand, and slave catchers and kidnappers of free Black people on the other. In addition, Philadelphia’s burgeoning textile industry needed cotton grown by enslaved Africans.”

Undaunted, Still continued aiding fugitives, risks be damned. After the Civil War, he became a coal merchant and a philanthropist.

St. Paul’s Lutheran Church located at 310 Quince St., another tour stop, was built and paid for by Black congregants. Black leaders had urgent meetings here in 1838 when Pennsylvania’s African American men faced the threat of disfranchisement. The men strategized in the church about how to keep their vote, Quinones said.

“The push to disenfranchise Black men came about because they voted in high numbers,” said historian Richard White, 67, president of the Black Docents’ Collective. “Their votes made the difference in an election in Columbia County, Pennsylvania.”

Legislators in Harrisburg feared that power. “Black Philadelphians, seeking a favorable outcome in Harrisburg, produced a series of documents showing that the city’s African Americans worked hard, owned property, paid taxes, and took care of its own,” Quinones said. “One of those documents was a handwritten detailed census carried out by community members themselves in 1838.”

The wealth of information in that census provided the foundation and the name of the walking tour: “The Philadelphia Black Metropolis.”

Influential Black men like abolitionists Robert Purvis (1810-1898) and James Forten (1766-1842), and other leaders also guided the production of “Register of Trades of The Colored People in The City of Philadelphia and Districts (1838)”. The register made clear that Black tinsmiths, plasterers, coopers, mechanics, barbers, caterers, whitewash men, pepper pot soup women, and more, plied their trades vigorously in the city. “The collective wealth of the community was about 40 million dollars,” Quinones said.

Despite this documentation and a pamphlet called “The Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Pennsylvania,” lawmakers approved killing the Black vote. Pennsylvania’s Black men would not vote again until the U.S. Congress passed the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in February of 1870, guaranteeing them that right.

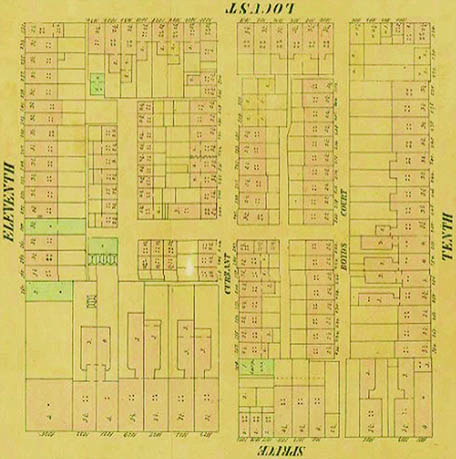

The tour includes Currant Alley, now Warnock Street, a bustling place in the 1830s.

“Over 60 percent of the children on Currant Alley went to school, and the Quakers’ Raspberry Street School for Colored children was within walking distance,” Quinones said. “A boardinghouse there sheltered Black residents, some of them probably freedom seekers. African American homeowners on Currant Alley included George Johnson, one of the richest waiter-caterers in the city. Historian Danya Pilgrim discovered that he had a contract with PSFS [Philadelphia Savings Fund Society].”

Resentment often smoldered due to African Americans’ prosperity.

“Blacks and whites lived in the same neighborhood, so whites saw Black businesses booming and Black people dressing well and riding in carriages,” Quinones said. That ill will boiled over in riots in 1834, 1838, 1842, and later. “For example, in 1834, Black homes and a church were destroyed,” she said. “One man was beaten to death in front of his wife and children.”

Discouraged, some families moved away, but Black neighbors in the area had a strong social infrastructure with churches, beneficial societies, and other organizations. For instance, in 1844, Hester “Hetty” Reckless (1776-1881) established the Moral Reform Retreat for Black women at 7th and Lombard, Quinones said. “This was a shelter by Black women for Black women.” Reckless wanted to protect the women from both slavery and sexual exploitation.

No one understood better than Reckless the need for such a refuge. Enslaved earlier in Salem City, New Jersey, she endured heartbreaking abuse. The wife of her enslaver, Colonel Johnson, reportedly knocked out Reckless’ front teeth with a broomstick. Reckless managed to slip away and board a stagecoach with her daughter, steeling in Philadelphia. Besides establishing the retreat, Reckless became an Underground Railroad agent.

In addition to the six stops on the tour, Quinones added related information not only about prominent Black Philadelphians, but their white counterparts. For example, she pointed out the Pennsylvania State Historical Marker at 258 S. 9th Street, the one-time home of Joseph Bonaparte (1766-1844), the older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte.

“Frenchmen, including Stephen Girard, used to party here,” Quinones said. “Girard reaped a fortune in the illegal opium trade with China,” she added, a fact spotlighted in books and essays like “American Merchants and the China Opium Trade, 1800–1840,” a June 2012 essay by Jacques M. Downes, published online by Cambridge University Press.

The tour has six stops and lasts about an hour. Most of the streets it covers have little traffic, making it safer. Wear sturdy comfortable shoes, given the cobblestones. To book a tour, please email: [email protected]. For more information, visit: www.blackdocents.com.

Leave a Comment